The final unit price of the Jakarta-Bandung railway, some US$52 million per kilometer, is higher than that of China’s high-speed rail, which cost between $17 million and $30 million per kilometer, as well as France’s, which cost $24 million per kilometer.

www.thejakartapost.com

Whoosh, here comes the deficit

The final unit price of the Jakarta-Bandung railway, some US$52 million per kilometer, is higher than that of China’s high-speed rail, which cost between $17 million and $30 million per kilometer, as well as France’s, which cost $24 million per kilometer.

W hen we reflect, in the years ahead, on President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo’s decade in power, we may recall it as a Big Bang for the country’s infrastructure – with all of that cosmic event’s chaotic consequences. State-run construction firms PT Wijaya Karya and PT Hutama Karya have found themselves in financial trouble for shouldering major government infrastructure projects, including toll roads and the Nusantara Capital City (IKN) project. The companies have been relying on state capital injections to make ends meet. And after enduring years of delays, the China-backed high-speed railway Whoosh finally began operations in the last quarter of 2023. For many, it was worth the wait. The first bullet train in Southeast Asia, connecting Jakarta and Bandung, has become a favorite among commuters and hit the 1-million-passenger mark within three months of opening. People have welcomed the reduced travel time between the two major cities, a journey that by car or regular train would take upward of three hours. But after the heady joy of breezing past towns and sawah on our 45-minute Whoosh ride, we have to pay the piper. We must face the reality of a debt that will drag on our state budget for years to come. PT Kereta Cepat Indonesia China (KCIC), the consortium responsible for the operation of Whoosh, expects the service to

face a deficit of Rp 3.15 trillion (US$200 million) in its first year of operation. Analysts say the deficit may continue for decades and will likely affect the state-owned enterprises (SOEs) behind the project, particularly railway firm PT Kereta Api Indonesia (KAI), which holds the largest stake in the railway on the Indonesian side. This year, KCIC expects to book Rp 2 trillion in revenue, more than 95 percent of which is projected to come from ticket sales. However, it will have to spend Rp 3.32 trillion to operate the service and another Rp 1.84 trillion to pay down loan interest and meet its tax obligations, according to a financial document seen by The Jakarta Post. With the population and economic growth in Jakarta, Bandung and the cities and regencies in between, there is growing demand for faster and more reliable public transportation. It’s clear we can’t rely solely on our increasingly traffic-jammed toll roads.

But before declaring Whoosh a success or considering expanding its network, the government must take an honest look at the project. Analysts have criticized the service as too expensive, and the Lowy Institute’s online publication The Intrepreter has noted that the final unit price of the Jakarta-Bandung railway, some US$52 million per kilometer, is higher than that of China’s high-speed rail, which cost between $17 million and $30 million per kilometer, as well as France’s, which cost $24 million per kilometer. In its early years, Whoosh may benefit from public enthusiasm for the novel service. But when that fades, the operator will have to rely on loyal customers with practical use cases, whose numbers may be limited. In recent months, Whoosh has served some

14,000 to 16,000 people a day, less than the approximately 21,000 people it accommodated daily during the Christmas and New Year holidays.

We know we must invest in public transportation, not more toll roads, but the government must plan carefully to ensure the debt it takes on is worthwhile and manageable. It must also efficiently design public transportation to connect with existing city landscapes, public facilities and the flow of people.

Such projects must not just

satisfy a leader’s personal ambitions or favor bilateral relations with certain countries. They should always serve the interests of the public, rather than transforming into a

burden that spans generations.

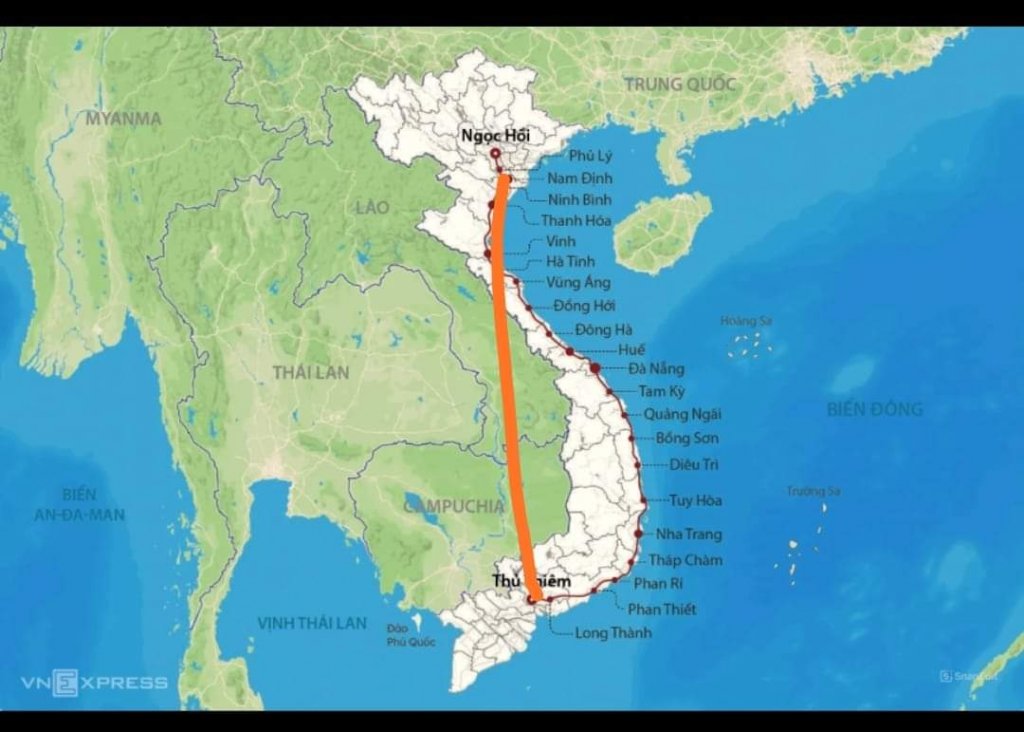

Chưa cần dự báo rách việc, chỉ cần nhạy cảm kinh doanh 1 tí, tính ra Hà Nội -SG vé 1 triệu 7 là biết hàng không mất 90% khách rồi, còn lại 10% cho nhà cụ nào kế sân bay hoặc trẻ lần đầu muốn bay thôi. Kể cả cụ nào có thẻ VIP máy bay mà bị trễ chuyến 1 lần thì thôi im luôn chứ nói ra kẻo thiên hạ chê cười.

Như cái Jakarta Bandung 142 km bằng Hà Nội - Thanh Hóa đấy, riêng nó là 6 triệu khách 1 năm ở 2024. Cụ nào rành tiếng Indo tìm hiểu xem xe khách với máy bay, tàu chậm ở bển thế nào rồi.

6 triệu ở đâu ra hử .

nhìn kỹ con số thống kê nào